During the wartime, letters were considered the only “link” for soldiers at the front line to express their feelings to people in the rear. Many of martyrs fell down in the war against the American troops to gain Vietnam’s independence and freedom. Thus, the martyrs’ letters to their families have been kept, and become memorabilia and sacred relics. Wartime letters given to the Museum by the martyrs’ families have been valuable objects and data sources for research on paper artifacts. All of them have made great contribution to their values and added more information about the collection of wartime letters currently preserved by the Museum. In wartime, anything could happen. On the boundary of life and death, people found it sometimes easy to make choices, i.e. moments of an ideological struggle with “humanities”. One of the cases we are presenting is the ideological struggle expressed in the two letters to his family by martyr Phạm Lương Điền.

On August 6, 1951, martyr Phạm Lương Điền was born in the house No. 7, Quarter 7, Võ Thị Sáu Street, Hàn Thuyên Town, Nam Định City. He came from a working family in which the father, Phạm Gia Hưu, was a worker in a textile factory, and the mother, Trần Thị Đáng, was a small trader. From 1964 to 1965, he studied in class 5B at Nguyễn Văn Cừ Junior High School; from 1965 to 1967, he attended Tran Dang Ninh High School; from 1967-1970, he was a pupil at Mỹ Lộc High School. In 1970, he joined the army and was sent to Battlefield B2. . .

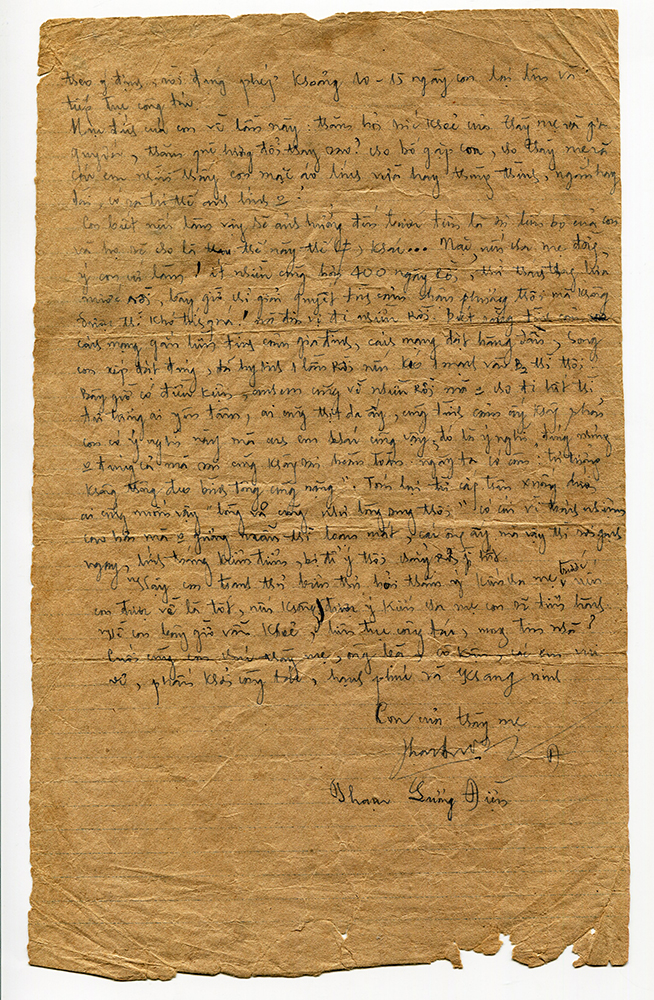

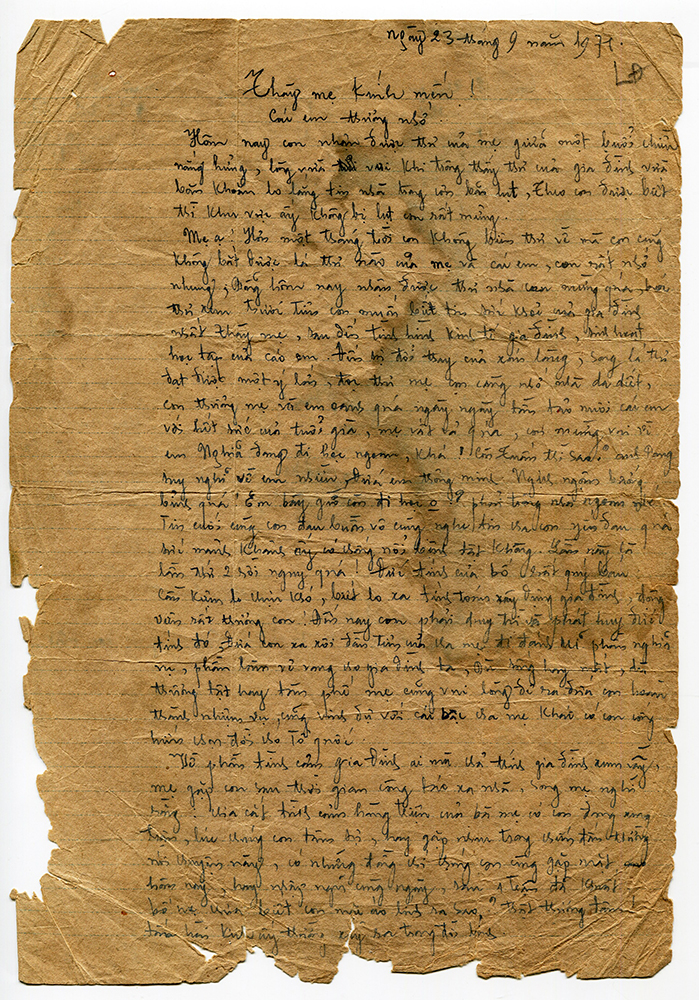

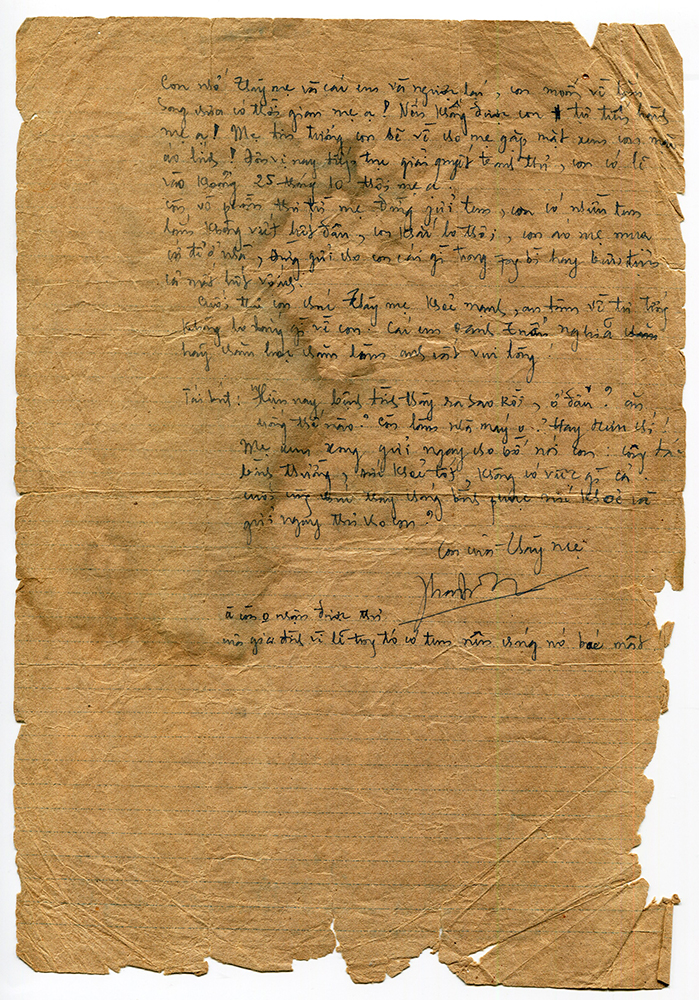

His two letters were sent to the family on September 3, 1971 and September 23, 1971. The first was written 20 days before the second right on the fierce battlefield of Hà Tĩnh province. However, they showed a great change in his thought.

In the middle of such a fierce battlefield time, any soldiers were more likely to miss their hometowns because they could not know when the death would call them. However, when the battle was more and more fierce, their army division allowed “no leave” for home visits. In the letter dated September 3, 1971, martyr Phạm Lương Điền wrote: “... so temporarily, no leave for home visit is allowed; and no one knows what it will be like and how the situation is going on.” In the soldier’s thought at that time, he just wished to return home for a visit even though something bad might happen. On a piece of notebook paper turning yellow with time were his wonders to the parents: “I have heard that our army division would allow “no leave” for home visits. I am now pondering too much and struggling in my mind... If the division does not accept any leave, should I solve it myself or how should I solve it? If I do it myself, am I too spirited? To prepare for it, I have to carry two steps. The first basic step is that I would ask for your opinions (in case the division allows no leave for home before we match for a battle far away). The second step is that with my own arguments, I would present my intention to the division. Whether they agree or disagree, I still do as I want. I would allow myself a ten to fifteen day leave, then return for my mission. My purpose for this visit is: to know about your health and the family members’, and changes in our hometown; to give you, my dear parents, and my siblings a chance to see whether my soldier uniform is fit or baggy, and short or long; and how I look like in the pose of a soldier."

Apparently, the purpose of a soldier in the wartime was extremely simple like that of a child in any family. He only hoped that his parents could see him once in a soldier uniform so that they could be proud of him in front of the relatives and neighbors. Afterwards, even if he had to sacrifice himself on the battlefield, he would not feel regret. Thereby, it is certainly not an impulse and transient desire but one that carries an ideological struggle. The soldier quite understood possible consequences when he was determined to perform it, an action breaking the army’s principles. In the letter, the son of this family confided, “I know if I take such an action, my progress will first be affected, and they may think of several assumptions… Who cares? With your permission, I’ll do it. I have spent over 400 days and experienced challenges in the fire and under the water of the battlefield. It is really difficult to feel peaceful if I can’t express my affection to you all in the rear. So far many comrades in my division have gone forever. I have known that the revolutionary sentiment is closely associated with the family one. The revolutionary course is always placed above all, and I put it in the right position when I sacrificed my family affection. However, I feel really uncomfortable if I have no home visit before continuously moving further to Battlefield B2. Now that we have some chances and many of us really want to take a leave for home visit. If we are not allowed to take it, we’ll have restlessness in mind. We, soldiers, are all just flesh and bone, we are quite reasonable to have such a family love. Anyone in life has this feeling. This thought is true, but we cannot say that it is completely right or wrong. As in a saying: “Once our thought is unclear, we suffer a heavy feeling on doing anything, even carrying a water bottle.” In a few words, from soldiers in higher positions to those in lower ones, they are “in the same boat”. However, thosein higher positions have more responsibilities. If they are not good samples, they are likely demoted. However, normal soldiers get no demotion but blame and criticism.”

Reading such words in the letter, some people may blame him for such soldier characteristics. However, these words are the most obvious and honest expression of the psychology of an offspring being a young man who temporarily put all his personal desires aside to respond to the common calling of the country. A full emotion for his ideal always remained in his heart. We can feel it in the letter written to his family on September 23, 1971, i.e. 20 days after the first letter. “Your first child has gone far away for the struggle against the American troops, partially completing his duty to the country and partially bringing a pride for the family. Whether I am alive or dead, injured or handicapped, I know that mum would feel happy to have given birth to a son who has tried to complete his duty. It is also a true honor for other parents whose children are devoted to their nation. As for the family love, anyone wishes that his family has a reunion, and the mother has a chance to meet her son during his service far away. However, the mother must have thought that it is worth separating the sentiments of millions of mothers from their children who are on battlefields. Whenever we have a chat or meet each other in a struggle, we often talk about this issue. Some of our comrades who we just met or who joined the army on the same day as us died after a struggle; and their parents didn’t know how they looked like in a soldier uniform. It is really strategic. That kind of dramas often happens in the life of soldiers.”

The psychological struggle in a soldier’s thought and perception expressed in the two letters by martyr Phạm Lương Điền somehow helps us understand that the war not only took place in the reality but also in the mind of those who were directly involved in the war. Regardless of belonging to any side on the battlefield, everyone must win the war in their own mind and make the best decision for themselves.

.jpg)